Dr. Emily Salisbury, an associate professor at the University of Nevada Las Vegas.

Oregon’s prisons are not the only facilities seeing more women every year. The number of women in jails nationwide has increased 14-fold since 1970, when three-quarters of counties didn’t have a single female inmate.

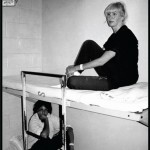

Fifty-six women currently are incarcerated in the Marion County jail. Numbers have fluctuated over the years, according to county data, but between 2011 and 2015, the percentage of female inmates jumped from about 14 percent to more than 17 percent.

Rural county jails are facing some of the biggest increases, according to a 2015 study by the Vera Institute of Justice.

If the increased severity and frequency of crime is not on the rise, what is behind the spike in female incarceration?

Salisbury said:

Much of what is driving this is not women becoming more violent or becoming more problematic, but the fact that our sentencing laws have changed. Certainly, the war on drugs has been a war on women, particular women of color.

She pointed to Measure 57 — a 2008 law that increased sentences for certain drug and property crime offenses frequently committed by women — as one of the contributors to the increase.

Sentencing strategies, like everything else in the criminal justice system, are based on the dynamics of male offenders, she said.

Salisbury added:

This, of course, doesn’t mean that women shouldn’t be punished or held accountable. Lawmakers and stakeholders need to take a look at what pathways led women to incarceration and recidivism in the first place.

During her study of about 300 women on probation, several reoccurring stories piqued Salisbury’s interest. Female offenders typically experienced childhood victimization, family violence, unhealthy relationships, unsafe housing and low levels of economic capital. Salisbury said different conversations, policies and practices are needed to address these underlying issues.

“If we don’t address core issues, we’ll continue to see them cycling through the system,” she said.

State officials recognize the unique needs of incarcerated women and are taking the steps to address them. In recent years, Oregon became one of 22 states to adopt the Women’s Risk Needs Assessment. And according to a statewide survey, Oregonians broadly support a preventative approach to incarceration. About two-thirds of those surveyed said they would support a preventive program over a punitive approach.

Going forward, Salisbury said she’d like to see judges and other community stakeholders educated on core issues facing female offenders and wide investment in female-responsive approaches. A careful look is needed at existing practices to make sure they aren’t backfiring because of gender.

“Contrary to what some people have said about justice-involved women needing a timeout in prison, I just simply don’t agree,” Salisbury said. “Women don’t need a time out, they need a way out.”

They need a way out of the insidious violence, trauma, victimization and discrimination that have plagued their lives, she continued, adding that these women will never escape the cycle without programs and interventions specific to their needs.

© Humane Exposures / Susan Madden Lankford