The Oklahoma Senate Appropriations Committee last week gave unanimous approval to a measure seeking to lower the nation’s highest female incarceration rate. Senate Bill 1278 would authorize the Office of Management and Enterprise Services (OMES) to enter into a Pay-for-Success (PFS) contract pilot program for those criminal justice programs that have had proven outcomes of reducing public sector costs associated with female incarceration.

The Oklahoma Senate Appropriations Committee last week gave unanimous approval to a measure seeking to lower the nation’s highest female incarceration rate. Senate Bill 1278 would authorize the Office of Management and Enterprise Services (OMES) to enter into a Pay-for-Success (PFS) contract pilot program for those criminal justice programs that have had proven outcomes of reducing public sector costs associated with female incarceration.

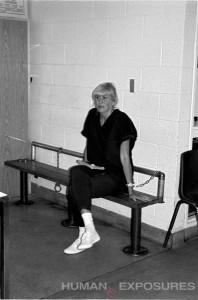

With a female incarceration rate nearly twice the national average, Oklahoma’s rate has topped the nation every year since 1994, except in 2003. Pathways to incarceration for Oklahoma women often begin early, with physical and sexual abuse, chaotic home environments and poverty. These childhood challenges often result in decreased educational attainment and can lead to substance abuse and addiction and mental illness. Domestic violence and adult victimization are other pathways to incarceration for women. Children with incarcerated parents have a significantly higher risk of being incarcerated in the future, continuing the cycle of incarceration.

Author of the Oklahoma legislation, David, R-Porter said:

Oklahoma’s history of imprisoning nonviolent women, rather than treating them, is expensive, ineffective and damaging to families. It’s important that we offer alternatives to incarceration to get these women rehabilitated and back to the workforce and their families. Incarceration and poverty are a vicious cycle in our state that we can stop by giving these women the counseling and education they need to get clean, find a job and be able to support themselves without returning to a life of drugs and crime.

With a PFS contract, the state negotiates with a program to deliver a specific outcome, such as reduced incarceration. Private philanthropy provides upfront funding. Once OMES verifies that the diversion or reentry program was successfully completed by a participant, the state would then re-pay a portion of the savings realized. Another benefit of using these contracts is that state payment will never exceed its savings created through the contracted programs.

Under SB 1278, only service providers which have provided programs that successfully diverted women from prison and which have the capacity (size, scale, budget) to serve at least 100 high-risk women would qualify for this initial PFS pilot.

The first PFS contract will be delivered in Tulsa County, which is the largest contributor to the female offender population in Oklahoma. Since fiscal year 2012, Tulsa County has outpaced Oklahoma County and the rest of the state in its female offender receptions.

David adds:

This is a win-win opportunity for Oklahoma. OMES can find nonprofits that have successfully helped currently and formerly incarcerated women gain the skills they need to become self-sufficient, productive members of society again.

This will help decrease the length of sentences and lower recidivism rates, which will in turn help address the state’s prison overcrowding problem and save the state millions in incarceration costs. Once released, these women will also become taxpayers, creating new revenue for the state, and they’ll hopefully be able to support their families and get off state assistance, saving the state even more money.

David said the bill was written for the Women in Recovery program in Tulsa, but others can apply. Any provider program must have at least $2 million in capital, according to the bill.

Family & Children’s Services’ Women in Recovery program began in 2009 as an alternative to incarceration for women who have drug and alcohol addictions and face prison sentences. The program has admitted about 300 women and has had 131 graduates. Currently, 102 are now participants.

Ken Levit is executive director of the George Kaiser Family Foundation (GKFF), which helped create Women in Recovery. He said the state saves money that would have been spent on incarceration when women successfully complete the program.

The Women in Recovery program offers an alternative to incarceration for Tulsa County judges, district attorneys and public defenders, by combining strict supervision within a comprehensive day treatment format for women with substance abuse problems. Participant requirements and programs include:

- Gender-responsive, trauma-informed substance abuse treatment and cognitive behavioral therapies;

- Employment and vocational training;

- Comprehensive individual and group treatment;

- Family reunification/parent-skill training;

- Transitional safe and sober housing;

- Intensive case management and basic needs;

- Employment and vocational training;

- Primary health and dental care;

- Linkage to community recovery support groups;

- Life skills, education, transportation, volunteerism;

- Wellness and stress reduction;

- Community integration

- Aftercare services post graduation.

A woman is potentially eligible to enter WIR if she is 18 years of age or older, is involved in the criminal justice system, is ineligible for other diversion services or courts, has a history or is at-risk of substance abuse and is at imminent risk of incarceration. Women with children are a high priority for program admission. With more than 300 women sent to prison from Tulsa County in fiscal year 2010, the need for alternatives is crucial.

Today Congress is moving on sentencing reform, which could further ease the pressure on female prisoners with children. In addition,

Today Congress is moving on sentencing reform, which could further ease the pressure on female prisoners with children. In addition,