Today Congress is moving on sentencing reform, which could further ease the pressure on female prisoners with children. In addition, they may benefit from less emphasis on harsh sentences for nonviolent offenses.

Today Congress is moving on sentencing reform, which could further ease the pressure on female prisoners with children. In addition, they may benefit from less emphasis on harsh sentences for nonviolent offenses.

Marc Mauer, executive director of the Sentencing Project, says:

The decline in women’s incarceration appears to be related to fewer drug offenders in prison. As harsh sentencing policies have begun to be scaled back, and diversion programs expanded, fewer women are now being sentenced to lengthy prison terms for lower-level drug offenses.

Since the early 1970s, the “war on drugs” led to a surge in the US prison population of both men and women. But percentagewise, women saw a greater increase. According to the Sentencing Project, between 1980 and 2010, the number of women in federal and state prison rose by 646 percent; from 15,118 to 112,797. If you count women in local jails, that brings the US total of female prisoners in 2010 to more than 205,000.

Now the trends are reversing. After peaking in 2009, the US prison population has declined annually–something that has been attributed to factors including the recession, and changes in public attitudes and in the courts. In 2011, the US Supreme Court upheld a ruling that ordered California to ease overcrowding in its state prisons.

Congress is now getting into the act. On January 30, 2014, the Senate Judiciary Committee voted for legislation aimed at reducing prison overcrowding further. In a bipartisan 13-to-5 vote, the panel approved the Smarter Sentencing Act,

which would substantially reduce mandatory minimums for some drug offenses and allow federal judges more discretion in determining sentences for nonviolent drug offenses?

The Act amends the federal criminal code to direct criminal courts to impose a sentence for specified controlled substance offenses without regard to any statutory minimum sentence if the court finds that the defendant does not have more than one criminal conviction. It also authorizes a court that imposed a sentence for a crack cocaine possession or trafficking offense committed before August 3, 2010, on motion of the defendant, the Director of the Bureau of Prisons, the attorney for the government or the court, to impose a reduced sentence as if provisions of the Fair Sentencing Act of 2010 were in effect at the time such offense was committed.

Courts must also reduce mandatory minimum sentences for manufacturing, distributing, dispensing, possessing, importing or exporting specified controlled substances. And it orders courts to formulate guidelines to minimize the likelihood that the federal prison population will exceed federal prison capacity, while it emphasizes the need to reduce and prevent racial disparities in sentencing.

Since women are more likely to be incarcerated for a nonviolent offense than men, they may benefit from the law disproportionately. Already, between 2009 and 2012, the female prison population dropped by 4.1 percent.

This trend has particular meaning for prisoners with children. In 2008, 52 percent of women in state prison and 63 percent in federal prison had at least one child under the age of 18, according to the Bureau of Justice Statistics. Six out of 10 women prisoners with children lived with their kids before incarceration.

Most kids don’t have physical contact with their mother while she is incarcerated, because women are often placed in facilities more than 100 miles from home, where visiting is both expensive and difficult. Collect phone calls from prison are expensive, and some mothers do not want to expose children to the prison environment and security procedures, which can be intimidating.

Bahiyyah Muhammad, a sociology professor at Howard University in Washington, D.C., who studied the children of incarcerated parents, suggests:

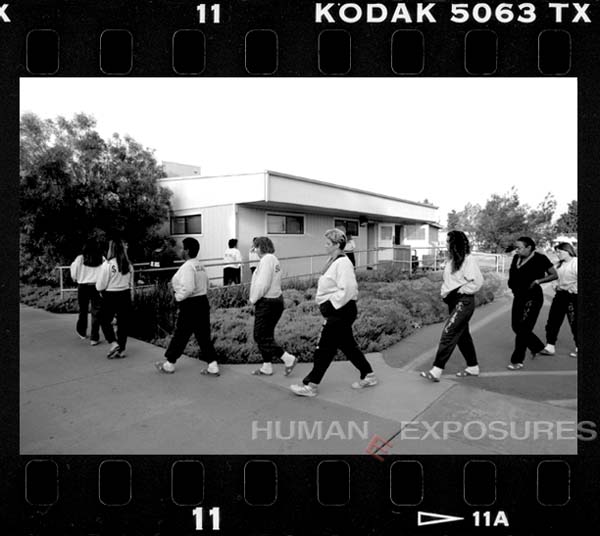

One solution would be to have offenders serve shorter sentences that are focused on drug treatment and education and that take place closer to their families. That way you keep the family together and allow them to have a role in this rehabilitation process.

A parental classification be implemented for convicted mothers) who have custody of their children, so they can serve their time at an institution designed for parents–that is, “friendlier” for kids.

I think we could save a lot of money if we used alternatives to punish nonviolent drug offenders, especially if they are parents. Parental incarceration has long-lasting effects on children.

Since the 1970s, the dramatic rise in the US prison population has put significant strain on the limited resources available to treat prisoners and to help ex-convicts reintegrate into the outside world.

The economic side of the penal system is something we look at a lot. In so many cases, the return of preventative programs vastly outstrips the return we see from imprisoning people. Our documentary is titled

The economic side of the penal system is something we look at a lot. In so many cases, the return of preventative programs vastly outstrips the return we see from imprisoning people. Our documentary is titled  Picture an inmate at the end of his sentence. The barred gates of the jail open up, and he steps out into the fresh air of freedom. Let’s assume this is an inmate who has been wholeheartedly reformed, kicked his bad habits, and has a determined attitude about rebuilding his life.

Picture an inmate at the end of his sentence. The barred gates of the jail open up, and he steps out into the fresh air of freedom. Let’s assume this is an inmate who has been wholeheartedly reformed, kicked his bad habits, and has a determined attitude about rebuilding his life.

HUMAN

HUMAN It is no secret that the American prison system is rife with problems. It is the personal stories of women in our penal system that led our own Susan Madden Lankford to create

It is no secret that the American prison system is rife with problems. It is the personal stories of women in our penal system that led our own Susan Madden Lankford to create