Forty months ago, in December 2010, The United Nations General Assembly adopted 70 comprehensive guiding Rules for the Treatment of Women Prisoners and Non-custodial Measures for Women Offenders, since known as The Bangkok Rules. These fill a long-standing lack of guiding standards for policymakers, legislators, sentencing authorities, prison staff, probation services, social welfare and health care services in the community, and non-governmental organizations, helping them all to better respond to the needs of women offenders

Forty months ago, in December 2010, The United Nations General Assembly adopted 70 comprehensive guiding Rules for the Treatment of Women Prisoners and Non-custodial Measures for Women Offenders, since known as The Bangkok Rules. These fill a long-standing lack of guiding standards for policymakers, legislators, sentencing authorities, prison staff, probation services, social welfare and health care services in the community, and non-governmental organizations, helping them all to better respond to the needs of women offenders

More than 625,000 women and girls are currently held in prisons worldwide. Of America’s 2.2 million-plus incarcerated persons, more than 200,000 are women and over one million other females are on probation and parole, according to the American Civil Liberties Union. America’s “War on Drugs” has had a devastating effect on women and men, alike: with only 5 percent of the world’s population, the U.S. currently has 25 percent of the world’s inmates. This means American prisons and jails hold about one third of the world’s incarcerated females.

Historically, the architecture, security, healthcare, protections, family contact and training for prisons were all designed for men. When the first prison for women was built in Indiana in 1873, it was intended just to separate the sexes, not to meet the special needs of female offenders.

In America, and around the world, women suffer more in prison than men do. Most female prisoners are housed with little consideration for their needs as women. Now there is a global guide for the treatment of female offenders called the Bangkok Rules.

Certain abuses happen to female offenders just because they are women. Over a decade ago I volunteered as an advocate for inmates in the HIV unit of Alabama’s Tutwiler Prison for Women. Despite earlier lawsuits brought against Alabama’s correctional system, abuses continue there. Today, federal investigators call Tutwiler Prison a “toxic house of horrors where repeated and open sexual behavior” is the norm. A Department of Justice investigation found that for two decades prisoners at Tutwiler have been subjected to all manner of humiliation.

The list of abuses includes officers forcing women into sexual acts in exchange for basic sanitary supplies, male guards openly watching women shower and use the bathroom, a staff-organized strip show and a constant barrage of sexually offensive language, according to the New York Daily News.

Across the country and around the world, Female offenders need special protections. As with the suspected Tutwiler Prison guards, many female offenders are subject to rape by male guards and female inmates. Like male inmates, women struggle with substance abuse and mental illness. More women are victims of prior physical and sexual abuse before entering prison than men. Community re-entry programs are rarely designed for women. Prisons are located far from family support, breaking a mother’s bond with her children and weakening her community network, thereby making re-entry more difficult.

In America, racial disparities in the criminal justice system lead to longer sentences for African-American and Latino women. The population of incarcerated African-American women has increased 800 percent over the last two decades. Since nearly 70 percent of African-American children live in female-headed households, the loss of that parent to incarceration often means placement of children in foster care.

More than 80 percent of women prisoners have an identifiable mental illness, and one in ten will have attempted suicide before being imprisoned. And the UN says that women are imprisoned for crimes for which men are not. Also, women offenders face greater stigma than men.

Women visit males in prison, but males rarely visit their female partners at the same rate. Nor do mothers visit daughters as often as they do their sons. When women return home, they are often rejected, and struggle to rebuild their lives socially and economically.

The Rules cover a wide range of areas for improvement, including admission procedures, healthcare, humane treatment, search procedures, children who accompany their mothers into prison, alternatives to imprisonment, global advocacy, justice for children, pretrial justice, prison conditions, rehabilitation and reintegration, torture prevention and women in the criminal justice system.

Below I selected 15 of the 70 rules that I considered especially worthy of mention.

Rule 2: Newly arrived women prisoners shall be provided with facilities to contact their relatives; access to legal advice; information about prison rules and regulations, the prison regime and where to seek help when in need in a language that they understand; and, in the case of foreign nationals, access to consular representatives as well.

Rule 4: Women prisoners shall be allocated, to the extent possible, to prisons close to their home or place of social rehabilitation, taking account of their caretaking responsibilities, as well as the individual woman’s preference and the availability of appropriate programs and services.

Rule 6: The health screening of women prisoners shall include comprehensive screening to determine primary health care needs, and also shall determine:

(a) The presence of sexually transmitted diseases or blood-borne diseases; and, depending on risk factors, women prisoners may also be offered testing for HIV, with pre- and post-test counseling; (b) Mental health care needs, including post-traumatic stress disorder and risk of suicide and self-harm; (c) The reproductive health history of the woman prisoner, including current or recent pregnancies, childbirth and any related reproductive health issues; (d) The existence of drug dependency; (e) Sexual abuse and other forms of violence that may have been suffered prior to admission.

Rule 12: Individualized, gender-sensitive, trauma-informed and comprehensive mental health care and rehabilitation programs shall be made available for women prisoners with mental health care needs in prison or in non-custodial settings.

Rule 15: Prison health services shall provide or facilitate specialized treatment programs designed for women substance abusers, taking into account prior victimization, and the special needs of pregnant women and women with children, as well as their diverse cultural backgrounds.

Rule 16: Developing and implementing strategies, in consultation with mental health care and social welfare services, to prevent suicide and self-harm among women prisoners and providing appropriate, gender-specific and specialized support to those at risk shall be part of a comprehensive policy of mental health care in women’s prisons.

Rule 19: Effective measures shall be taken to ensure that women prisoners’ dignity and respect are protected during personal searches, which shall only be carried out by women staff who have been properly trained in appropriate searching methods and in accordance with established procedures.

Rule 20: Alternative screening methods, such as scans, shall be developed to replace strip searches and invasive body searches, in order to avoid the harmful psychological and possible physical impact of invasive body searches.

Rule 22: Punishment by close confinement or disciplinary segregation shall not be applied to pregnant women, women with infants and breastfeeding mothers in prison.

Rule 25: a) Women prisoners who report abuse shall be provided immediate protection, support and counseling, and their claims shall be investigated by competent and independent authorities, with full respect for the principle of confidentiality. Protection measures shall take into account specifically the risks of retaliation. b) Women prisoners who have been subjected to sexual abuse, and especially those who have become pregnant as a result, shall receive appropriate medical advice and counseling and shall be provided with the requisite physical and mental health care, support and legal aid. c). In order to monitor the conditions of detention and treatment of women prisoners, inspectorates, visiting or monitoring boards or supervisory bodies shall include women members.

Rule 28: Visits involving children shall take place in an environment that is conducive to a positive visiting experience, including with regard to staff attitudes, and shall allow open contact between mother and child. Visits involving extended contact with children should be encouraged, where possible.

Rule 31: Clear policies and regulations on the conduct of prison staff aimed at providing maximum protection for women prisoners from any gender-based physical or verbal violence, abuse and sexual harassment shall be developed and implemented.

Rule 45: Prison authorities shall utilize options such as home leave, open prisons, halfway houses and community-based programs and services to the maximum possible extent for women prisoners, to ease their transition from prison to liberty, to reduce stigma and to re-establish their contact with their families at the earliest possible stage.

Rule 47: Additional support following release shall be provided to women prisoners who need psychological, medical, legal and practical help to ensure their successful social reintegration, in cooperation with services in the community.

Rule 61: When sentencing women offenders, courts shall have the power to consider mitigating factors such as lack of criminal history and relative non-severity and nature of the criminal conduct, in the light of a women’s caretaking responsibilities and typical backgrounds.

Today Congress is moving on sentencing reform, which could further ease the pressure on female prisoners with children. In addition,

Today Congress is moving on sentencing reform, which could further ease the pressure on female prisoners with children. In addition,

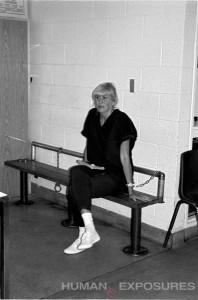

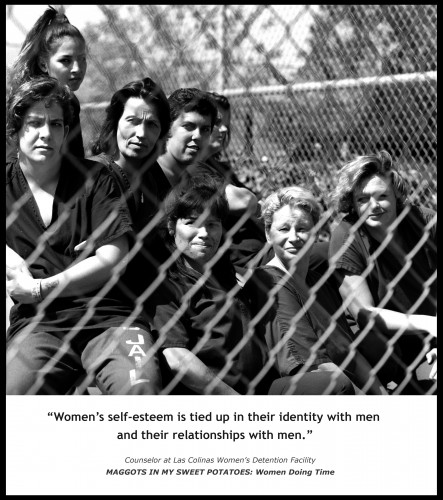

Oxytocin can benefit incarcerated women by reducing the stress one experiences in uncomfortable circumstances. Humane Exposures founder, writer Susan Madden Lankford, contends that this is a normal “clutching together” of the women who end up in prison open dayroom or patio experiences.

Oxytocin can benefit incarcerated women by reducing the stress one experiences in uncomfortable circumstances. Humane Exposures founder, writer Susan Madden Lankford, contends that this is a normal “clutching together” of the women who end up in prison open dayroom or patio experiences.