As of 2016, the most recent data available, Mississippi ranked 14th out of all states for the rate of female incarceration.

Researchers and advocates from The Sentencing Project, the National Council for Incarcerated and Formerly Incarcerated Women and Girls, and two regional organizations based in Nashville and San Francisco sought to contextualize national and regional statistics with projects they’ve undertaken in specific cities and regions in a web panel Tuesday.

Most of these women have young children, she added — over 60 percent of women in state prisons have at least one child under age 18.

At a national level, the growth rate of incarcerated women doubles that of men, though women make up only about seven percent of the U.S. prison population. And African-American and Latina women are currently imprisoned at twice and 1.4 times the rate of white women, respectively.

In contrast to men, more than half of whom are imprisoned for violent offenses, most women are imprisoned for nonviolent crimes, per The Sentencing Project. Only 37 percent of women in state prisons in 2016 were convicted of a violent crime.

These numbers are mostly driven by local and state policies, thus yielding the wide range of imprisonment rates across states, Ghandnoosh said. At 149 per 100,000, Oklahoma ranks first, while Massachusetts and Rhode Island are tied for last at 13 per 100,000.

Within Mississippi’s system, disparities have emerged between resources allocated for female and male inmates, as the Atlantic reported in April. The Mississippi Department of Correction’s website lists 13 vocational opportunities for men, such as auto mechanic and welding technology, and only five for women, including cosmetology and “Family Dynamics,” which is described as an expanded form of a home-economics class.

Other MDOC programs tailored for women include a recent re-entry workshop, backed by Arianna Huffington, businesswoman and co-founder of the Huffington Post, that uses “principles routinely applied in the corporate world.”

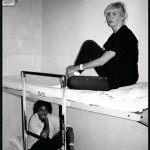

All women in MDOC state prisons are held at the Central Mississippi Correctional Facility in Rankin County.

Andrea James, founder and executive director of the National Council for Incarcerated and Formerly Incarcerated Women and Girls, posed the question:

How do we shift the system? It involves finding ways to pull back from the current system and really engage communities in taking back their power. Engage communities in being a part of the process of making decisions about what does justice look like for us? What do we want our communities to look like?

Nowlan, of the San Francisco-based Young Women’s Freedom Center, provided a case study of work still needed for young, incarcerated women, even in California: “Still no housing, still in poverty, still having to do survival sex work,” she said. She cited incidents in which snatching phones or stealing laundry soap turned into felony charges.

Research conducted by the Freedom Center into the past 25 years has shown a “huge correlation” between homelessness and incarceration, foster homes and juvenile justice systems, Nowlan added.

Oleta Fitzgerald, Southern regional director for the Children’s Defense Fund in Jackson, links the plight of incarcerated women of color in Mississippi, particularly, to a dearth of economic opportunity, citing poverty as a driving force behind the state’s incarceration rate.

“When you intersect poverty, gender and race, you’ve got yourself something,” Fitzgerald told Mississippi Today.

That Mississippi is the poorest state in the nation, ACLU of Mississippi executive director Jennifer Riley Collins adds, means that most women who enter the criminal justice system are economically disadvantaged with little education, few job skills, and sporadic employment histories.

Women leaving prison, Riley outlined in a statement, must stay clean and sober, return to a primary caretaker role for their children, earn a livable wage, obtain reliable childcare and transportation, and find safe and sober housing for themselves and their children. And all of this occurs while they try to meet requirements of community supervision and additional demands of other public agencies such as child welfare.

Women need to be provided with a basic safety net: transportation, community spaces, housing, healthcare, education, employment, and economic security. Without a safety net, women often are forced to return to a life of survival and are not afforded the opportunity to be restored.

In organizing efforts to address the disruptive effects of incarceration on women and children, organizers have found it crucial to include the experiences of the incarcerated themselves.

“We don’t do anything — not one thing — without first reaching to the women and girls and (families) who are on the inside of the prison bunk,” James said.

© Humane Exposures / Susan Madden Lankford