An inscription of the Code of Hammurabi. (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

Restorative Justice, which has been practiced in many cultures for more than 4000 years, is now making inroads in the United States. It seeks to largely replace a collective justice that is tainted by racial discrimination, by billions in corporate profit, by the warehousing of our most vulnerable, by maintaining a school-to-prison pipeline and by the practices of expecting punishment and isolation for all involved when crime occurs. Instead, it is actually rehabilitative.

Restorative justice (sometimes called reparative justice) focuses on the needs of the victims and the offenders, as well as the involved community, instead of satisfying abstract legal principles or punishing the offender. Victims take an active role in the process, while offenders are encouraged to take responsibility for their actions and to repair the harm they’ve done—by apologizing, returning stolen money and/or performing community service.

It considers crime to be an offence against an individual or community, rather than the state. Restorative justice that creates dialogue between victim and offender shows the highest rates of victim satisfaction and offender accountability.

Restorative justice is not a new concept. It was practice in ancient Sumeria around 2060 B.C., requiring offender restitution for violent crimes. From about 1700 B.C., Babylon’s Code of Hammurabi prescribed restitution for property offences. Also in the Old Testament’s Five Books of Moses, restitution was ordered for property crimes. Indigenous tribes around the world practice Restorative Justice, and it is the main juvenile justice model in New Zealand today. A modern example of it with adults is the “Truth and Reconciliation Commission” in post-Apartheid South Africa.

Retributive justice began to replace such systems after the Norman invasion of Britain in 1066 A.D. when William the Conqueror’s son, Henry I, detailed offenses against the “king’s peace.” By the end of the 11th century, crime was no longer regarded as injurious to persons, but rather was seen as an offense against the state. This view, tragically, has persisted since then.

Throughout the U.S., programs are working in the Rehabilitative Justice area, and legislation action is in the works in Massachusetts and Florida. Backed by Congressman Bobby Scott, D-Va., with support from Senator Mary Landrieu, D-La. and Senator James Inhofe, R-Okla., the Youth Promise Act, brought forth by many co-sponsors and led by The Peace Alliance, focuses on dismantling the prison-to-school pipeline by effectively implementing programs and providing education and tools that derive from Restorative Justice principles. It will fund evidence-based violence-prevention and intervention practices, empower local control and community oversight, save taxpayer money and provide measurable data that backs up the successes.

The U.S. is the world’s incarceration leader, imprisoning 754 people per 100,000—2.3 million in total—at a public cost of $63 billion per year. Colorado and Ohio lock up more of their citizens than dictatorships such as Pakistan and Libya, and many more than allies including England (154) Canada (117), Germany (85) and Japan (59). Virginia Senator Jim Webb said, “We are either the most evil people in the world, or there is something fundamentally wrong with our criminal justice system.”

Colorado recently passed a Restorative Justice Pilot Projects law that in four judicial districts sets up a fund for restorative justice with a $10 surcharge on all violations excluding traffic. It focuses on youth diversion and strong data collection, research and education to complement a growing general statistic that proves its efficacy.

In reports from Longmont, CO’s Police Department’s Restorative Justice Programs and the Longmont Community Justice Partnership, Master Police Officer Greg Ruprecht says:

These youth programs show exponential drops in recidivism (at the moment the rate is 10%, compared to 60-70% nationwide) and high participant satisfaction. Perhaps even more poignant is the tens of thousands of dollars per case that is saved from diverting youth from incarceration.

Thousands of prominent public figures, including Michael Moore, Cameron Diaz, Jamie Foxx, Scarlett Johansson, Rev. Al Sharpton, Will Smith, Kerry Washington, Rev Jesse Jackson, John Hamm, Russell Brand, Margaret Cho, Ron Howard, Chris Rock, Mark Wahlberg and Deepak Chopra have signed a letter to President Obama urging criminal justice reform and support for the Youth PROMISE Act (Prison Reduction through Opportunities, Mentoring, Intervention, Support and Education) and other reforms. The letter says, in part:

We believe the time is right to further the work you have done around revising our national policies on the criminal justice system and continue moving from a suppression-based model to one that focuses on intervention and rehabilitation.

“We are proud of your accomplishments around these issues—specifically your leadership on gun control, your investments in “problem solving courts,” your creation of the Federal Interagency Reentry Council, your launching the National Forum on Youth Violence Prevention and your prosecution of a record number of hate crimes in 2011 and 2012.

“We recommend, under the Fair Sentencing Act, extending to all inmates who were subject to 100-to-1 crack-to-powder disparity a chance to have their sentences reduced to those that are more consistent with the magnitude of the offense. We ask your support for the principles of the Justice Safety Valve Act of 2013, which allows judges to set aside mandatory minimum sentences when they deem appropriate.

Restorative justice can be handled in a courtroom or within a community or nonprofit organization. In social justice cases, impoverished victims such as foster children are given the opportunity to describe their future hopes and make concrete plans to transition out of state custody, in a group process with their supporters.

In the community, concerned individuals meet with all parties to assess the experience and impact of the crime. Offenders listen to victims’ experiences, preferably until they are able to empathize with them. Then they speak to how they decided to commit the offense. A plan is made to prevent future occurrences, and for the offender to address the damage to the injured parties. All agree. Community members then hold the offender(s) accountable for adherence to the plan.

In addition to serving as an alternative to civil or criminal trial, restorative justice can be applicable to offenders who are currently incarcerated. This assists with the prisoner’s rehabilitation and eventual reintegration into society. By repairing the harm to the relationships between offenders and victims, and offenders and the community, that resulted from crime, restorative justice seeks to understand and address the circumstances which contributed to the crime, in order prevent recidivism, once the offender is released.

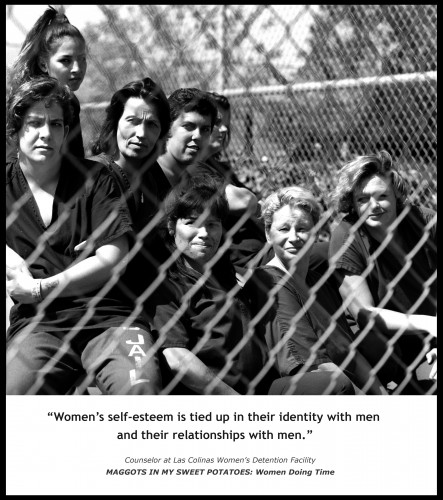

Oxytocin can benefit incarcerated women by reducing the stress one experiences in uncomfortable circumstances. Humane Exposures founder, writer Susan Madden Lankford, contends that this is a normal “clutching together” of the women who end up in prison open dayroom or patio experiences.

Oxytocin can benefit incarcerated women by reducing the stress one experiences in uncomfortable circumstances. Humane Exposures founder, writer Susan Madden Lankford, contends that this is a normal “clutching together” of the women who end up in prison open dayroom or patio experiences.