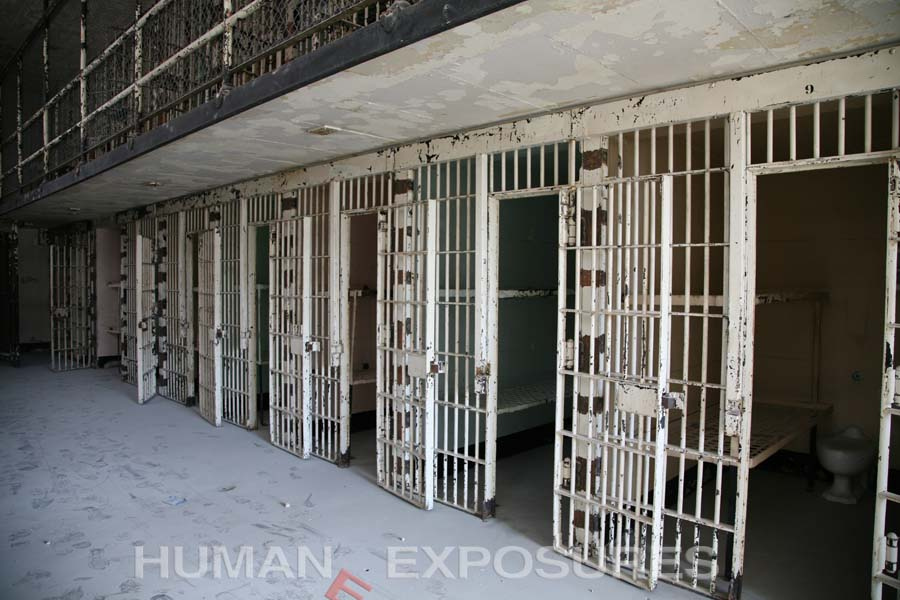

Over the last 20 years, Oklahoma has become the country’s capital of female incarceration, with 127 of every 100,000 women behind bars, double the national rate of 63 per 100,000. It’s a situation so pronounced that even the Oklahoma Department of Corrections has had to acknowledge it: “Oklahoma has consistently ranked first in the rate of female incarceration nationally.”

But Oklahoma’s prisons aren’t filled with the fairer sex because Oklahoma women  pose more of a threat than women elsewhere; the state simply penalizes women’s actions more forcefully—much more forcefully. At the same time, social safety nets have been cut away, limiting women’s options for other means of survival.

pose more of a threat than women elsewhere; the state simply penalizes women’s actions more forcefully—much more forcefully. At the same time, social safety nets have been cut away, limiting women’s options for other means of survival.

According to Susan Sharp, a professor at the University of Oklahoma and the author of Mean Lives, Mean Laws: Oklahoma’s Women Prisoners, drug possession and drug trafficking are the top two reasons for the ballooning women’s prison population. And indeed, of the 1,152 women entering Oklahoma’s prison system in 2013, 52.6 percent were arrested for a drug offense, with 26.2 percent ultimately sentenced for possession and 16.6 percent for distribution. Keep in mind that Oklahoma often ratchets up the charges by counting possessing, distributing, transporting or manufacturing a certain quantity of drugs as trafficking. “Five grams of crack or twenty grams of meth can be charged as a trafficking act,” Sharp explained.

In addition, conditions in Oklahoma often push women down the path toward prison. Oklahoma ranks among the bottom 16 states for women’s mental health, meaning that Oklahoma women report experiencing poor mental-health conditions, including stress, depression and eating disorders, at a higher average than in many other states. In 2015, it ranked among the bottom 10 states for women’s economic security and access to health insurance and higher education.

The result of all these tangled, competing forces is a vicious cycle in which the women who have the least access to social and economic independence, health insurance and mental health treatment are the most at risk for imprisonment. And, as in other parts of the country, women of color tend to suffer disproportionately: in a state where black people make up only 7.7 percent of the entire population, nearly 20 percent of the women’s prison population is African-American; Native American women are 13 percent of the prison population, but Native people of all genders are only 9 percent of the state population.

Yet, rather than address these disparities, Oklahoma continues to lock up the women who are most vulnerable to them.

At the boot camp, inmate “Gillian” recalled,

They treated us like dogs. Barked orders at us and insulted us. Came in in the middle of the night and tore up the dorm a couple of times and we had to run around the track with our mats on our back.

The boot camp offered her no programs to address her addiction, help her find a job or regain guardianship of her son. “When I got out, I was simultaneously enraged and depressed by the further mess my life had become and almost immediately relapsed,” she wrote in a recent letter from prison. She got pregnant, failed to report to her probation officer and was soon arrested. This time, her father paid her bail, allowing her to give birth outside and leave her newborn son with him before being sent to prison for a year and a half.

For women like Gillian, prison does not merely mean the loss of liberty; it also means a loss of their children, sometimes permanently. In 1997, Congress passed the federal Adoption and Safe Families Act, stipulating that the state begin proceedings to terminate parental rights if a child had spent 15 of the past 22 months in foster care.

Susan Sharp conducted a survey of incarcerated mothers for Oklahoma’s Commission on Children and Youth. She found that nearly 10 percent of the women participating had children in foster care, placing them at greater risk for permanent separation from their parents.

Even when they know that their children are safe with other family members, incarceration still takes its toll. Gillian did not see her older son for over 10 years. She has seen him a handful of times within the past few years, but she laments that they remain “virtual strangers.” Although her father brings her younger son to visit regularly, he too has grown up without his mother.

To some degree, Oklahoma recognizes that it has a problem. To combat the drastic increase in incarceration caused by the War on Drugs (as well as the accompanying costs), counties have turned to drug courts, which send women (and men) charged with a nonviolent drug crime to treatment programs, rather than prison. However, failing to complete the stipulations of the drug court can lead to prison, sometimes for a lengthier sentence than if a person had initially pled guilty. Oklahoma has a 42 percent rate of drug-court failure, Sharp noted in her book. In an interview with The Nation, she added that the average sentence for failure is 74 months. Most of these failures, she points out, are for flunking a urine test or not paying court-imposed fines. It’s an “alternative,” in other words, that is also a pathway to prison.

Sentencing is another area in which state is beginning to recognize the need for change. “We definitely need to revisit lengthy sentences, especially for drug crimes and low-level property crimes,” Sharp told The Nation. In February 2015, state legislators introduced House Bill 1574, which allows for a 20-year sentence instead of requiring life without parole for a third drug offense (so long as the two prior convictions are not drug trafficking). And on May 6, 2015, Governor Mary Fallin signed it into law. But the 55 people serving life without parole for drug offenses won’t be going home, because the bill is not retroactive.

So what could stem the flow of women to prison?

Although few people ask the women, they themselves may be the best source of wisdom for how to disrupt Oklahoma’s womb-to-prison pipeline. After years behind prison walls, these women understand how their lives—and their lack of opportunities—helped snare them in the criminal-justice net. And they know what needs to change for women in the state. Reflecting on their experiences, they see the holes in the state’s social safety net that would have kept them from falling out of society and into prison. They also know the solutions that would help keep other lives from being destroyed. But these solutions are not quick fixes; instead, they are systemic changes that might take decades, if not generations, and would refashion Oklahoma dramatically.

For Gillian, keeping out of prison would require a comprehensive change in state policies.

To keep women out of prison, so much would have to change in the current system, Oklahoma would be unrecognizable. This is a generations/decades-long endeavor. Everyone thinks drug treatment, more and better, is the answer. It is part of the solution, but decriminalization is probably more important. How many alcoholics are in prison for anything other than DUI? That’s because the cost of their drug of choice is not prohibitive. Nobody robs a liquor store so they can buy liquor.