Auditor General Michael Ferguson just released

Ferguson acknowledges there are rehabilitation programs aimed at Indigenous offenders behind bars, but they are not offered “in a timely manner.” He added that corrections staff aren’t prepared to take the “social history factors” of Indigenous offenders into consideration when it comes to case management.

“The result is that fewer Indigenous offenders are prepared for parole than non-Indigenous offenders,” said Ferguson.

Ferguson also said that when Indigenous offenders are released directly from maximum and medium security prisons, it is often “without gradual and structured transition back into society.”

His report notes that 69 per cent of Indigenous offenders are released at their statutory release dates.

“It’s a serious analysis of what the problems are around preparing Indigenous people for release,” said Catherine Latimer, executive director of the John Howard Society, who adds that she was surprised at the number of Indigenous offenders being released directly from prisons. “It’s better that they cascade down to minimum security and participate in the graduated release mechanism.”

If offenders are released through that graduated process — with support and supervision — they’re less likely to re-offend and end up back in prison, Latimer said.

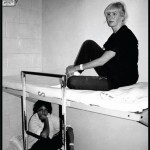

The report also raises the alarm about the rising number of Indigenous inmates, particular women.

“In the prairie region, almost half of offenders in custody are Indigenous,” the report said, noting the overall Indigenous population grew by 25% in the past decade — compared to the non-Indigenous prison population, which has actually declined slightly. The report also said Indigenous women are the fastest-growing population in federal institutions — making up 36% of female offenders in custody.

The report includes eight recommendations for fixing the problems, including:

* Increasing ways to consider an offender’s Indigenous social history.

* Offering more culturally specific rehab programs.

* Transitioning Indigenous offenders to lower-security institutions before they are released.

The CSC has agreed to address all of the recommendations, the report said.

“Those of us who are interested in this issue will need to be vigilant just to make sure that progress is being made,” said Latimer.

© Humane Exposures / Susan Madden Lankford