During the leadership meeting, presenters offered a graphic of how the system needs to change. Up until recently, getting people housing and services has been fragmented – go one place for food, another for temporary shelter. Organizations were working in silos. Housing was given out on a first-come-first-served basis to people who met certain requirements. Some people who stay at Brother Francis Shelter say they’ve been waiting for months and sometimes years for housing and have had to apply to multiple agencies. They just give up.

Michele Brown,president of the United Way of Anchorage, has played a key role in developing the community plan to end homelessness. She said the new plan calls for something different:

The heart of the local plan to make homelessness rare, brief, and non-reoccurring is tailored services to everyone’s unique needs because everyone has their own story and their own reasoning. But Anchorage also needs housing stock. We need to have more affordable housing. And you need to stay with people when they are in that housing long enough to have them become self-sufficient.

That means more outreach to learn about each person’s needs and desires, so they can be quickly matched with appropriate resources.

Though the coordinated plan is just starting now, the city has found housing for about 400 people since mid-2015. But it’s too soon to say if all of them will be able to keep that housing.

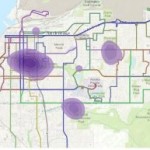

Part of the Anchorage Plan to End Homelessness includes an open data portal with things like heat maps showing where many homeless camps are reported to be.

Community leaders at the mayor’s meeting – many of whom work directly in the field – sat in small groups discussing what needs to happen before this plan can really be effective.

Jim Nordlund is the executive director of NeighborWorks Alaska, which provides affordable housing. He said his organization doesn’t have time to track what every other nonprofit is up to:

I know what we do at NeighborWorks Alaska, but I’m not really sure what all the other organizations do. And somewhere somebody should put a matrix together or something to figure out, ‘Ok, this is what all the organizations do,’ and see where the gaps are.

The day after the first leadership team meeting, I went a few blocks northeast of City Hall to the Brother Francis Shelter and Bean’s Café campus. Most people I spoke to there had no idea there was a new plan for helping people get out of homelessness.

A man who only goes by Birdman said he liked aspects of the plan, like the idea of getting people into housing even before they’re sober and making sure they have support networks in place. But he said that should only happen for a limited period of time.

But Birdman, who has been waiting for housing for three years, says providing highly subsidized or free housing only works on a temporary basis:

If we permanently house them, all we’re doing is enabling them. We’re saying, ‘It’s ok.’ Smack them on the wrist and keep going. No.

He himself has been looking for housing for three years, though he remains hopeful. He said people should have to work for their housing.

But Samantha Coyle, who is also homeless, said the city just needs to get roofs over people’s heads, without any restrictions:

If somebody’s got their own place, let them have the dignity and respect to make their own decisions. Too many rules, especially about visitors, lead people to leave their housing and return to the streets.

She said providing housing first will solve many of the problems and will reduce the number of people abusing substances. But if she was really in charge of the plan to end homelessness? She’d build more affordable housing. Lots of it, she said.

Luckily for Coyle, that’s already part of the plan.

© Humane Exposures / Susan Madden Lankford