In 2011, under mounting pressure to decrease the prison population, the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR) created the Alternative Custody Program (ACP) designed to forge a path for low-level female inmates to return home (under electronic surveillance), care for their children and reintegrate into their communities.

Cynthia sought ACP admission after getting her paperwork straightened out and applying three times, but she was was denied. The explanation? She was told she needed a teeth-cleaning before her application could be processed. Another woman was denied because of a computer error: Her dentistry was up to date, but a bureaucrat hadn’t changed her status, so she remained behind bars. Michelle, who has four children at home, was denied ACP because of a mistake in classification—her crime was embezzlement, but it was mistakenly classified as “violent,” rendering her ineligible.

In the offices of California Coalition for Women Prisoners (CCWP), letters have piled high from women who want to return home to their families and repent for their crimes. But very few of the eligible inmates are given a real chance to take advantage of the opportunities that ACP promised.

In one of the letters, an inmate named Anna, in prison for identity fraud, wrote:

I know I’ve made mistakes in my life, but I’m ready for a change. Yes, I’ve been in and out of prison, but don’t only look at my record; look at what I did and all my programs.

She has not been released.

Misty Rojo, the program coordinator at CCWP, has received reports from women who were denied release because they had a pit bull as a pet and because they received medication for a treatable medical condition like high blood pressure.

Before the women are released under ACP, they’re subject to a pre-release interview that includes sensitive questions about their histories of abuse and other mental anguish. The Justice Depaartment has determined that at least half of all female inmates have been victims of physical or sexual abuse and one-third have been raped prior to incarceration, and that appearing to harbor lingering psychological trauma from this abuse can prevent release. Even worse, the people asking these questions aren’t licensed therapists.They intentionally ask questions that cause the women to break down into tears and then accuse the women of being “mentally unstable,” meaning they are not eligible for release.

That’s what an inmate named Theresa claimed happened to her in a letter she wrote to CCWP explaining that she “was not prepared for what took place in my ACP classification hearing.” Theresa met all of the criteria for ACP and had no disciplinary actions. She participated in programs like Alcoholics Anonymous and anger management. But in her hearing she was asked about her suicide attempts as a minor as well as her childhood and adult molestation and rape. She felt blindsided by the process and dejected at the result, which was a denial of her ACP application.

These stories help to illustrate why out of the estimated 4,000 women eligible for ACP, only 420 have been released in the three years the program has been active. California’s prisons are overflowing—so why is the state trying to keep its women inmates behind bars?

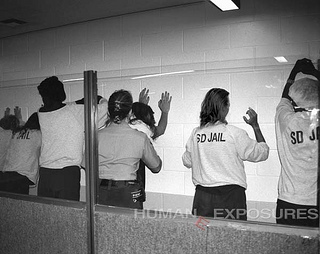

Women are the fastest-growing segment of America’s prison population, and more than half of them—at least in California—are non-violent offenders. Women, along with gender-nonconforming inmates, are also some of the most vulnerable inside prison; rates of inmate-on-inmate sexual violence are greater among women than men. It is estimated that 75% of incarcerated women are the primary caretakers of their children, meaning that their imprisonment leaves a trail of disaster for their families.

In the rancorous policy debates over California’s deplorable prison system, women’s prisons have frequently fallen by the wayside. Their overcrowding leads to a range of obvious problems , from overuse of solitary confinement and more frequent lockdowns (since there are too many inmates for the staff to control) to a lack of basic supplies and unsanitary conditions. But perhaps the most severe indirect consequence of overcrowding is poor medical care for the inmates. In December 2013, a court-appointed panel of medical experts issued an independent report condemning the conditions at CCWF, citing a litany of institutional deficiencies.

More shockingly, an investigation last summer by the Center for Investigative Reporting discovered that nearly 150 female inmates were given unauthorized sterilizations between 2006 and 2010 at three California women’s prisons. A new bill just signed by Governor Brown supposedly outlaws the practice at last.

Two of the prisons have been the target of scrutiny for poor medical care for almost 20 years, but instead of releasing female prisoners who are unlikely to pose harm—thus, potentially alleviating some of these issues—Governor Jerry Brown recently signed a $9 million/year contract with GEO Group, the second-largest private prison contracting company, to take over a prison facility in McFarland, California that will house about 260 women (with an option to double its size). Prison p.r. claims that the facility will boast services like job training, drug programs and other therapeutic interventions, although there is no guarantee that transferred inmates will be able to continue any of their current programming.

But the move is not an auspicious one. While the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation doesn’t have the best track record, it looks like a luxury hotel compared to GEO Group, which is the subject of hundreds of lawsuits for violence, mistreatment and poor medical care in its facilities.

In 2010, the ACLU filed a lawsuit on behalf of an epileptic Texas man who died from an untreated seizure while in solitary confinement. GEO Group was criticized for the abysmal conditions in a Mississippi juvenile facility by a federal judge, who held that the private company allowed “a cesspool of unconstitutional and inhuman acts and conditions to germinate.”

On top of concerns about privatized prisons, the latest outcry over the proposed McFarland facility crystallizes the ongoing problem of California’s women’s prisons: facilities plagued by scandals and problems that remain largely out of the public view.

While the GEO contract might temporarily alleviate overcrowding, it doesn’t solve the real problem, which would be to allow the release of non-violent offenders and maintain the programs that help these women reintegrate into their communities. (ACP provides no assistance for women seeking employment or housing.)

The popularity of Orange Is the New Black has drawn attention to the plight of women in prison. Still, it is difficult for these women to speak up about their treatment, because they have felt so consistently ignored by prison authorities, who operate in a system dominated by hyper-masculine principles. The CDCR, like all prison regimes, lacks accountability, because its decisions are always shrouded under the guise of “public safety”– something no politician seems bold enough to question.

Women inmates are less likely to riot or institute hunger strikes, which emboldens the CDCR to ignore them, because they are less in the public eye. These women suffer from what is called a “double invisibility,” hidden from the public’s eyes because no one will take the time to listen.