Polling was conducted in June 2017, and involved a sample of 1,042 California residents.

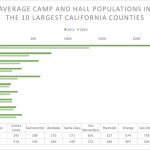

According to the most recent data available from California’s Board of State and Community Corrections (BSCC) in December 2015, 110 juvenile detention camps and halls in California held 4,841 youth.

An analysis of BSCC data found that county-run juvenile detention facilities were only 38.4 percent full.

That number of incarcerated youth in California has dropped off in recent years, mirroring a steep decline in youth arrest numbers in California.

David Muhammad, executive director of the National Institute for Criminal Justice Reform and former chief probation officer for Alameda County, acknowledged that crime trends have led to a decrease in youth incarceration. But he also cited greater awareness of the impact of youth incarceration, particularly among leaders across the state.

Muhammad said:

Even amongst correctional supervisors, board of supervisors members and judges who may not necessarily be card-carrying progressives, they now have information that says detention is harmful to young people, it is very costly, it is also ineffective. That is not a political statement.

In Los Angeles County, which possesses the largest juvenile justice system in the state, the average daily population of its camps and halls slid from 2,270 in 2011 to 1,311 in 2015. Today, Los Angeles County probation officials have indicated that the number may be half as much as in 2015.

But in some counties, the state is still adding beds in youth incarceration facilities. According to a recent count from the BSCC, around 418 are in the process of coming online soon, thanks to money allocated for counties to spend on the construction of new jails under Senate Bill (SB) 81 in 2007.

Under SB 81, also known as California’s juvenile justice realignment bill, the legislators moved the responsibility for holding youth offenders from the state to county-run facilities. The bill also set aside money for two rounds of long-term funding for new or refurbished youth incarceration facilities.

Several of those facilities from the first wave of funding have opened recently, such as the 106-bed Alan M. Crogan Youth Treatment and Education Center in Riverside County, which began serving youth past March thanks to nearly $25 million dollars from the state.

California awarded $16 million to Tuolumne County to build the Mother Lode Regional Juvenile Detention Facility, a 30-bed juvenile hall that was inaugurated in April in Sonora, Calif.

And last month, Los Angeles County opened doors on the $52 million Campus Kilpatrick, a 120-bed facility in Malibu that probation officials hope will provide a more therapeutic approach to working with youth.

Before the facility opened, the Probation Department announced a plan to shutter six juvenile camps in L.A. County over the next two years in response to the mounting costs, which have risen to $247,000 per year per youth.

A coalition of advocates—including the Children’s Defense Fund, Youth Justice Coalition and others—have called on the Probation Department to further its efforts to cut back its use of juvenile camps and halls, which held more than 3,000 youth on an average day in 2007.

“We urge that as many camps as appropriate are closed to better serve youth and their families – through reducing waste, increasing the probation system’s efficiency and efficacy, repurposing the facilities for alternative use, and shifting cost-savings into community-based investments,” reads a letter penned by coalition members.

Several more juvenile detention facilities are underway using money from SB 81, including facilities being constructed in Santa Clara and Monterey Counties. Brian Goldstein, director of policy for the San Francisco-based Center on Juvenile and Criminal Justice, remains concerned that the money allocated to large juvenile detention facilities could be better used to help high-needs youth at the community level.

He cited a campaign by Salinas-based young advocacy organization MILPA to reduce the number of beds in a new juvenile hall in Monterey County from 150 to 120. The facility is scheduled to open in September 2019. According to Goldstein, that’s an example of how some counties in California are starting the slow process to dial back youth incarceration.

Goldstein said:

In the past, the measurement for what makes communities safer was one-dimensional; it was how many people are incarcerated in these facilities. Now we have a much broader sense of what public safety means, what public health means. I think that’s why you’re seeing more Californians support systematic reform that’s necessary for the state and our communities.

© Humane Exposures / Susan Madden Lankford