A study of feminist therapy and incarcerated women advised that feminist psychotherapy is essential to the well-being of women of marginalized women, especially incarcerated women. Although some feminist principles have been applied to programming for women in prison, major feminist inroads have yet to be made into correctional systems.

Study author Susan Marcus-Mendoza writes:

We need to work towards a fully feminist paradigm of corrections that empowers incarcerated women and transforms women’s correctional facilities into rehabilitative environments.

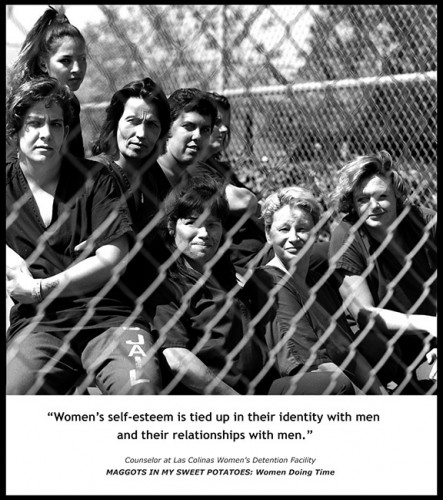

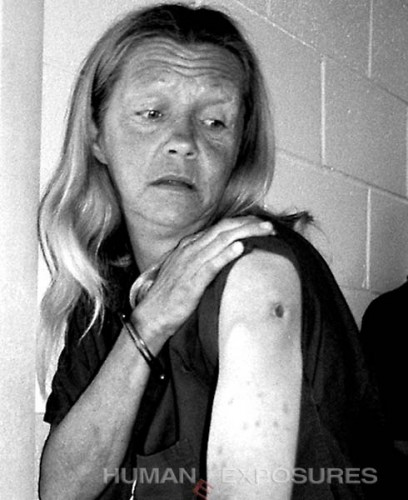

Women in prison are among the most marginalized members of our society. Their lives behind bars are not within their control. Every hour of their day is scheduled for them, and access to everything inside and outside of the prison is strictly regulated. Such important aspects of life as food, medical care, reading materials, psychological treatment, exercise, educational opportunities and family contact are dictated by the prison policies and staff. Most of them are trauma survivors and victims of violent crimes who come from economically deprived, oppressive backgrounds.

Studies have shown abuse rates among female inmates as high as 85%, and therefore these women are likely to experience Complex Trauma and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. Additionally, most women in prison have been victims of one or more types of violence both as children and adults. One study found higher reported rates of homelessness, abuse, living in foster care or other agencies, having parents with substance abuse problems, having family members in prison and receiving public aid, as well as lower rates of living with both parents and being employed prior to incarceration.

A study by Kinsler and Saxon summed up the problem thusly:

We are incarcerating people who cope with their own prior abuse through three common pathways: depression, anger and violence, and substance abuse. In many ways, we are incarcerating last generation’s abuse survivors, rather than treating them.

Our corrections system is more focused on punishment and containment than treatment and rehabilitation, even though women’s prisons are full of those in serious need of treatment.

What is currently required is a gender-responsive model, which involves creating an environment and offering programs that reflect an understanding of incarcerated women’s lives and recognizes women’s unique pathways to crime. Such social and cultural factors as race, socio-economic status, gender disparities and ethnicity are taken into account in developing interventions for abuse, domestic violence, substance abuse, and other issues pertinent to incarcerated women. The emphasis in these interventions is on self-efficacy and skill-building.

Feminist therapy is informed by feminist political philosophies and analysis and grounded in multicultural scholarship on the psychology of women and gender, which leads therapist and client toward strategies and solutions advancing feminist resistance, transformation and social change in daily personal life, and in relationships with the social, emotional and political environments.

Feminist therapy is a subversive project that promotes growth and healing for women in distress. Working together, therapist and client strive to undermine oppressive patriarchal structures that serve as sources of distress and hinder women’s growth. This is accomplished by analyzing gender, power, and social locations/multiple identities as strategies for comprehending how and why a person feels distress or behaves in dysfunctional ways.

Feminist therapists in prisons must focus on issues of power and oppression, empowering women to take responsibility for their choices, as well as helping incarcerated women to deal with the oppressive setting of the prison, and to see the patriarchal structure of society. Feminist therapists in prisons must also make sure that they assist women in dealing with such issues as racism and homophobia, as experienced both inside and outside the prison. On an institutional and societal level, feminist therapists should actively question and work to change policies and practices that support oppression. They can do this by educating the prison staff about the issues faced by women in prison and advocating for feminist therapeutic interventions that are both effective and non-punitive. Therapists can advocate for development and implementation of gender-specific programming, and the hiring of women of color and bilingual therapists and correctional staff.

Marcus-Mendoza concludes:

I believe that feminist therapy in women’s prisons is a crucial undertaking, and that feminist therapists should and can play a central role in transforming women’s prisons. I believe feminist therapists also need to do advocacy inside and outside of the prison to change policy and laws. The feminist therapist, should therefore not only work in the therapy room but should examine every aspect of the prison experience and work with staff and administration to bring about positive transformation. This feminist therapist is an advocate and an activist, giving voice to the oppressed women who may be punished for speaking for themselves.

![trendsinJJreport[1]](http://humaneexposures.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/trendsinJJreport1.jpg)