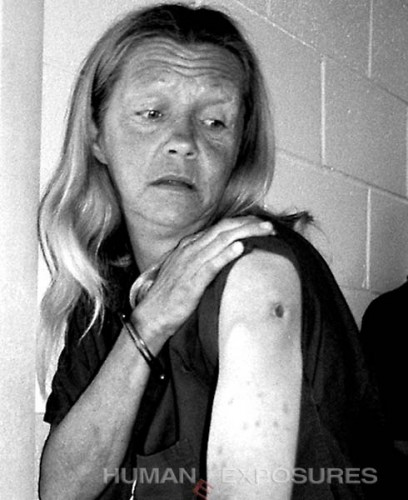

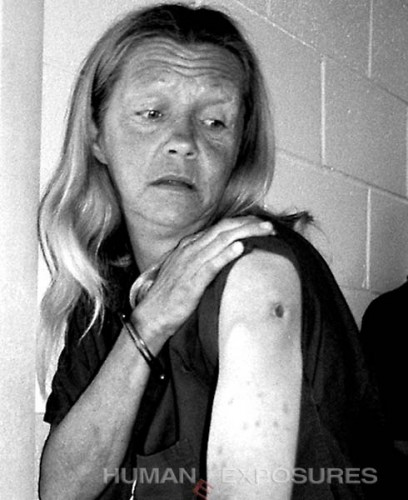

Photo by Susan Madden Lankford

Reports on eating disorders in prison are surprisingly scarce. But these reports do suggest an unreported high rate of eating disorders in a women’s prison in the US, with a disturbing number developing for the first time during incarceration.

One reason that prisoners may under-report their symptoms is that inducing vomiting and possession of diet pills, laxatives and diuretics would subject them to disciplinary action. A critical factor seems to be that the American penal system appears to be more brutal, controlling and punitive than other penal systems in the developed world. The Texas heat , for example, can be brutal; 12 inmates died of heat-related causes in Texas prisons since 2007, and of 111 prisons in the system, only 21 are fully air-conditioned.

A major reason US prisons are so terrible has been the the privatization of the penal system. Douglas Stephenson, Licensed Clinical Social Worker and former mental health consultant to a local county jail, said that the jail he worked with had been previously run by the county sheriff’s department, which employed graduates of the police academy with additional training and experience in corrections. The sheriff’s department protested greatly when the county commissioners decided to turn it over to the Corrections Corporation of America, which hired poorly trained, young, inexperienced personnel who were poorly paid and received few job benefits.

Stephensen wrote:

As I directly observed the way the guards dealt with the inmates, screaming, yelling at them, sometimes pushing them around, it seemed that they didn’t know the difference between a ‘jail’ and a ‘concentration camp’. In contrast, graduates of the police academy learned the difference early on over at the sheriff’s dept.

“The one thing the companies that make up the prison-industrial complex – companies such as Community Education or the private-prison giant Corrections Corporation of America – are definitely not doing is competing in a free market. They are, instead, living off government contracts. To the extent that private prison operators do manage to save money, they do so by employing fewer guards and other workers and by paying them badly. And then we get horror stories about how these prisons are run.

Rates of mental illness in US prisoners have been reported to be two to four times higher than in members of the general public. Borderline personality disorder was found to be quite common, and twice as high for women prisoners compared to men. In male and female offenders newly committed to prison it is a pervasive pattern of instability in interpersonal relationships, self-image, and affects, with marked impulsivity in binge eating.

The few international studies that explored eating problems in female prisoners revealed high levels of restrictive and bulimic eating pathology and unhealthier attitudes toward weight and shape than among women in the general population. In a study of 124 female inmates receiving mental health services at a women’s prison in Oregon, the prevalence of current bulimic symptoms was 40%, and the lifetime prevalence rates for key criteria of bulimia and anorexia were 25.8% and 5.6%, respectively. In a study of UK female prisoners, 25% were found to be at risk for an eating disorder, a prevalence rate twice that observed in a non-eating disordered community sample.

Numerous studies and anecdotal evidence suggest that there is a social contagion or mass hysteria factor. “Fat talk” – conversation about hating their bodies and wanting to be thin – has become an easy way for women to promote a relationship with other women. In many colleges, binge-and-purge parties provide an alternative to sororities for becoming part of a social network and an equivalent initiation rite – the female version of a beer party, with popularity measured by the extent of bulimic behavior.What may begin as a social ritual may precipitate the onset of an eating disorder in a vulnerable person who, on trying it, finds that purging offers a release of tension. In a Canadian study, when a female college freshman was assigned at random to a bulimic roommate, she was five times more likely to have tried purging by the year’s end than a freshman not assigned to a bulimic roommate.

A locked setting may have a complex meaning for an inmate with an eating disorder, largely around control issues. Because a sense of control is paramount in those with eating disorders, issues around control will loom much larger in prisons, where inmates have little sense of control over their lives and basic bodily functions may be scrutinized and regulated. Under these circumstances, the development of a potentially life-threatening illness becomes a highly charged means of asserting control over correctional staff. Patients with eating disorders tend to be quite resistant to treatment under the best of circumstances, and so attempts to treat women with eating disorders in a prison environment present a formidable challenge.

A basic goal in treatment of an eating disorder is for the patient to attain sufficient internal control over thoughts, feelings and behavior, something that the usual prison environment impedes by asserting such control over inmates’ lives. Even a prisoner were to be transferred to a less-controlling environment, such as a therapeutic community or open hospital, the prison environment will already have had its destructive impact. To treat inmates with eating disorders, the structure of prison life would have to be radically altered from the day of admission.

The only environment in which effective treatment might occur is one which immediately upon admission places an inmate in an open ward psychiatric hospital for criminal offenders that operates as a female therapeutic community. Although therapeutic communities have been recommended for those with addictions, mentally disordered offenders, and criminal offenders (but not for psychopaths), there have been few scientific studies of their value in eating disorders.