Students experiencing homelessness struggle to stay in school, to perform well, and to form meaningful connections with peers and adults. Ultimately, they are much more likely to fall off track and eventually drop out of school more often than their non-homeless peers.

Students who experience homelessness are more likely than their non-homeless peers to be held back from grade to grade, have poor attendance or be chronically absent from school, fail courses, have more disciplinary issues and drop out of school. These negative effects are amplified the longer a student remains homeless.

Students who experience homelessness are disproportionately minorities, and LGBTQ students are heavily over-represented in the unaccompanied youth population.

The National Center on Family Homelessness reports that 75 percent of homeless elementary school students performed below grade level in reading and math. That number rose to 85 percent for high school students.

Students who are homeless struggle with learning disabilities and emotional difficulties at higher rates than their housed peers. Homeless students also face the challenge of being both over- and under-identified for special education.

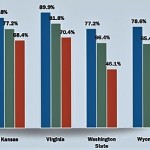

Only five states – CO, KS, VA, WA, WY – now report high school graduation rates for homeless students. In all five, rates lag well behind grad rates for all students, even other low-income students. The gap between all students and homeless students in Washington State, for example, was 31 percentage points in 2014.

Only five states – CO, KS, VA, WA, WY – now report high school graduation rates for homeless students. In all five, rates lag well behind grad rates for all students, even other low-income students. The gap between all students and homeless students in Washington State, for example, was 31 percentage points in 2014.

In the study 82 percent say being homeless had a big impact on their life overall, 72 percent on their ability to feel safe and secure, 71 percent on their mental and emotional health, 62 percent on their physical health, and 69 percent on their self-confidence. 60 percent say it was hard to stay in school while they were homeless; 42 percent say they dropped out of school at least once.

Half say they had to change schools during their homelessness, and many did so multiple times. 62 percent say the process was difficult to navigate, citing proof of residency requirements (62 percent), lack of cooperation between their old and new schools (56 percent), the need for medical records (50 percent), being behind on academic credits (48 percent), needing a parent or guardian to sign forms (48 percent) and transportation to and from school (48 percent).

One of the most significant challenges to meeting the needs of homeless youth is simply identifying them. Two thirds of the youth participating in this study (67 percent) say they were uncomfortable talking with people at their school about their housing situation and related challenges. Parents may not want to report their living situation for fear of losing custody of their children. And unaccompanied youth fear being placed into the foster care system.

The fluidity of youth homelessness further compounds the difficulties of identifying homeless students. Young people frequently drift between different living arrangements, or fall in and out of stable housing repeatedly.

78 percent of youth surveyed for this report say homelessness was something they experienced more than once. 94 percent say they stayed with other people rather than in one consistent place; 50 percent say they slept in a car, park, abandoned building, bus station or other public place. 47 percent say they were homeless both with a parent and alone.

When students were asked what they needed, they cited as very or fairly important having someone to talk to or check in with for emotional support (86 percent), connecting with peers or maintaining friendships (86 percent), participating in school activities including sports, music, art, and clubs (82 percent).

58 percent say their schools did only a fair or poor job or should have done more to help them stay in and succeed in school. Just 25 percent say their schools did a good job helping them find them housing.

61 percent say they were never connected with any outside organization while homeless; 87 percent of those who were connected found the help valuable.

The report recommends that to help homeless students, people at the school, community, state and national level must:

1) Ensure that the Every Student Succeeds Act amendments on identifying and serving homeless students in the McKinney-Vento Act and Title I part A are fully implemented in states, schools, and districts;

2) Expand outreach efforts to inform homeless students and families of their rights and to raise community awareness;

3) Ensure that schools have the resources to actively engage with homeless students to help them stay in school;

4) Build connections between community organizations and schools, then connect homeless students to those outside supports;

5) Set community and national goals around outcomes and graduation rates for homeless students, and use data to drive progress; and

6) Increase efforts to provide more affordable housing.